In any criminal case in the state of Minnesota, the prosecution has the burden of proving the guilt of a person accused of committing a crime. When eyewitnesses, video or other forms of evidence directly proving the facts are not available, prosecutors often rely upon circumstantial evidence. Sometimes, particularly with crimes involving intentional conduct, the only way to prove what a person intended may be circumstantial evidence.

A recently filed decision from the state court of appeals proves how the use of circumstantial evidence may prove to be problematic for the state. A careful analysis by the appellate court in State of Minnesota vs. Mayson Kellon Lueck, (Mille Lacs County District Court File No. 48-CR-19-1766), filed on April 19, 2021, of the evidentiary rules governing circumstantial evidence offers a glimpse into an aspect of criminal trials you do not get from TV dramas or the movies.

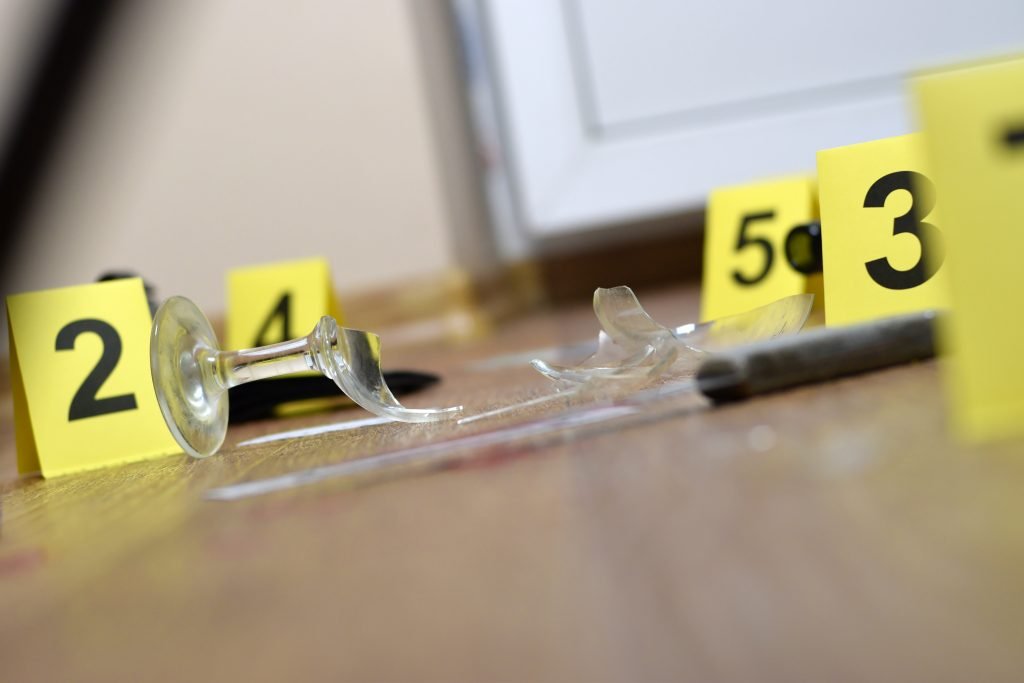

A broken window leads to criminal charges

The facts of the case are relatively uncomplicated as is the crime the offender was charged and convicted of committing. February 2017, found Mayson Kellon Lueck as the sole occupant of cell M-2 in a housing unit of the Mille Lacs County jail known as “M-Block.” The door to the cell had two clear, glass windows, which figure prominently in the prosecution of Mr. Lueck.

A corrections officer on duty in M-Block testified at trial that after delivering dinner to Mr. Lueck, he briefly heard the sound of banging and kicking coming from the housing unit. The officer testified that loud sounds coming from the cell area was common as a means for inmates locked in their cells to communicate with each other.

The officer investigated and noticed one of the door windows for cell M-2 had been broken. Broken glass was strewn about the area inside and outside the cell. Mr. Lueck was observed standing in the middle cell M-2 and was ordered to sit on the bed as officers entered the cell. According to testimony at trial, the following observations were made by the officers:

- Lueck complied with directions given by the officers.

- A rectangular dinner tray was on the floor of the cell.

- The tray had a towel wrapped around one of its short ends.

- Lueck did not have any glass fragments on him.

- Lueck was not bleeding and appeared to be uninjured.

- Lueck appeared upset, but he cooperated with the officers and quietly remained seated on the bed as directed.

The state charged Mr. Lueck with fourth-degree criminal damage to property, which is a violation of Minn. Stat. §609.595, subd. 3 (2016). The statute makes it a crime to intentionally cause damage to property reducing its value by less than $500 without the owner’s consent. He was convicted after a jury trial and sentenced to serve a 90-day jail sentence and pay restitution to the state in the amount of $318.64, which was the cost of replacing the glass window.

Issue raised on appeal

The lawyers handling the appeal for Mr. Lueck argued that the evidence the prosecution introduced at trial failed to support the conviction. The court of appeals reversed the conviction because inferences drawn from the circumstantial evidence could have been something other than the guilt of the defendant.

Court’s analysis of circumstantial evidence

The intent of a person accused of violating Minn. Stat. §609.595, subd. 3 (2016) is an essential element of the offense that must be proven by the prosecution. According to the decision of the appellate court, Minn. Stat. §609.02, subd. 9(3) (2016) defines “intentionally” as used in the criminal damage statute as meaning that a person “either has a purpose to do the thing or cause the result specified or believes that the act performed by the actor, if successful, will cause the result.”

The prosecution relied on circumstantial evidence to prove facts from which jurors could infer the state of mind of Mr. Lueck and his intent to commit the crime. The court of appeals noted that it must go through a two-step process when analyzing the sufficiency of circumstantial evidence.

The first step in the process involves identifying what was proven by the circumstantial evidence without questioning the jury’s reliance on it. The second step requires a court to determine, independent of the conclusions reached by jurors, whether what was proven was consistent only with guilt. In this case, the court determined that a conclusion other than guilt could have been reasonably drawn from the circumstances proven by the evidence.

The court summarized the circumstances proven by the prosecution evidence at trial as follows:

- The window was unbroken when the officer brought dinner to the cell.

- Noises were heard coming from M-Block.

- A broken window was observed by the officer investigating the noises.

- The only occupant of cell M-2 was Mr. Lueck.

- The occupant of cell M-1 could not have broken the glass.

- No one other than Mr. Lueck had access to the cell.

- Broken glass was observed on the cell floor along with a tray wrapped in a towel.

- Lueck cooperated with corrections officers.

- Lueck was uninjured.

- Cost of repair of the window was $318.64.

The state argued in support of the conviction that the circumstances, including the tray wrapped with the towel, were consistent with an inference that Mr. Lueck intentionally broke the glass. The court disagreed and pointed toward the lack of any evidence that Mr. Lueck used the tray to hit the window. In fact, no evidence was offered about how the window broke or the type or strength of the glass. The facts proven, according to the court, did not rule out a reasonable inference being drawn that the breaking of the glass was accidental and not intentional.